Illuminati History

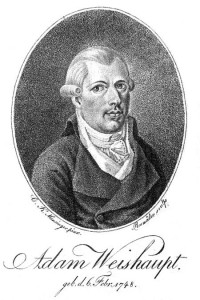

Little is known about the Illuminati’s history and inner workings. Historians know that the group was founded on May 1, 1776 in Ingolstat, a city in Bavaria. Founder Johann Adams Weishapt, a 28-year-old philosopher and law professor, meant for the group to be called the Order of Perfectibilists. Instead, the group was formally declared the Order of the Illuminati.

Created during the social movement of the enlightenment era, the Illuminati’s founding ideals were to combat prejudice, religious influence on social and governmental activities, and power abuse by the government. The group encouraged gender equality and supported women’s rights and education.

Ingolstadt, Germany, home to the founding of the Order of the Illuminati in 1776.

Membership of the group was varied, including many well known intellectuals from the region, politicians, authors and some Freemasons. Membership is rumored to have grown quickly, and with more than 2,000 members from across Europe.

Within one year of the Illuminati’s existence in Ingolstat, governmental oppression worked to tear down the organization. By 1777, Bavarian rule was passed to Karl Theodor, who governed the region for 22 years. Theodor’s leadership of Bavaria began with a ban on secret societies and organizations that met behind closed doors.

By 1784, Illuminati leader Weishapt fled Bavaria after the government intercepted many of his writings. Considered radical and seditious, Weishapt left the country, leaving behind his work and the Illuminiti for safe haven in Gotha, Germany. Many of the seized documents were later published by the Bavarian government, an anti-secrecy move that reflected the throne’s ideas about transparency. After writing several pieces about the Illuminati’s work and mission from exile, Weishapt died in November of 1830.

By 1785, a governmental proclamation further vilified the membership in secret groups and sent remaining members of the Illuminati into hiding, renouncing involvement. At this point in historical writings, no further information about the Order of the Illuminati exists.

Following the Order’s collapse, writings from across Europe insinuated the Illuminati’s survival, suggesting conspiracies and involvement with the French Revolution and other social upheavals. Articles and texts reverberating these ideas circulated from Europe to the United States, and additional spins were put on the rumors. The stories evolved to including demonic activities, working for and with demons, and quest for world domination.

Fifty years after Weishapt’s death and nearly 100 years after the Illuminati’s recorded demise, an attempted revival occurred. Theodor Reuss, a journalist, spy and freemason (among many other titles) tried to jump start the order in 1880. The initial attempt failed, and Reuss tried again in 1888. With two unsuccessful attempts (for reasons unknown), Reuss went on to become part of the Ordo Templi Orientis, another secret society.

Many modern groups across the globe claim to be descendants of the Bavarian Order of the Illuminati, though no evidence can prove such. Many groups use the Illuminati name in their group titles, but relationship cannot be determined.